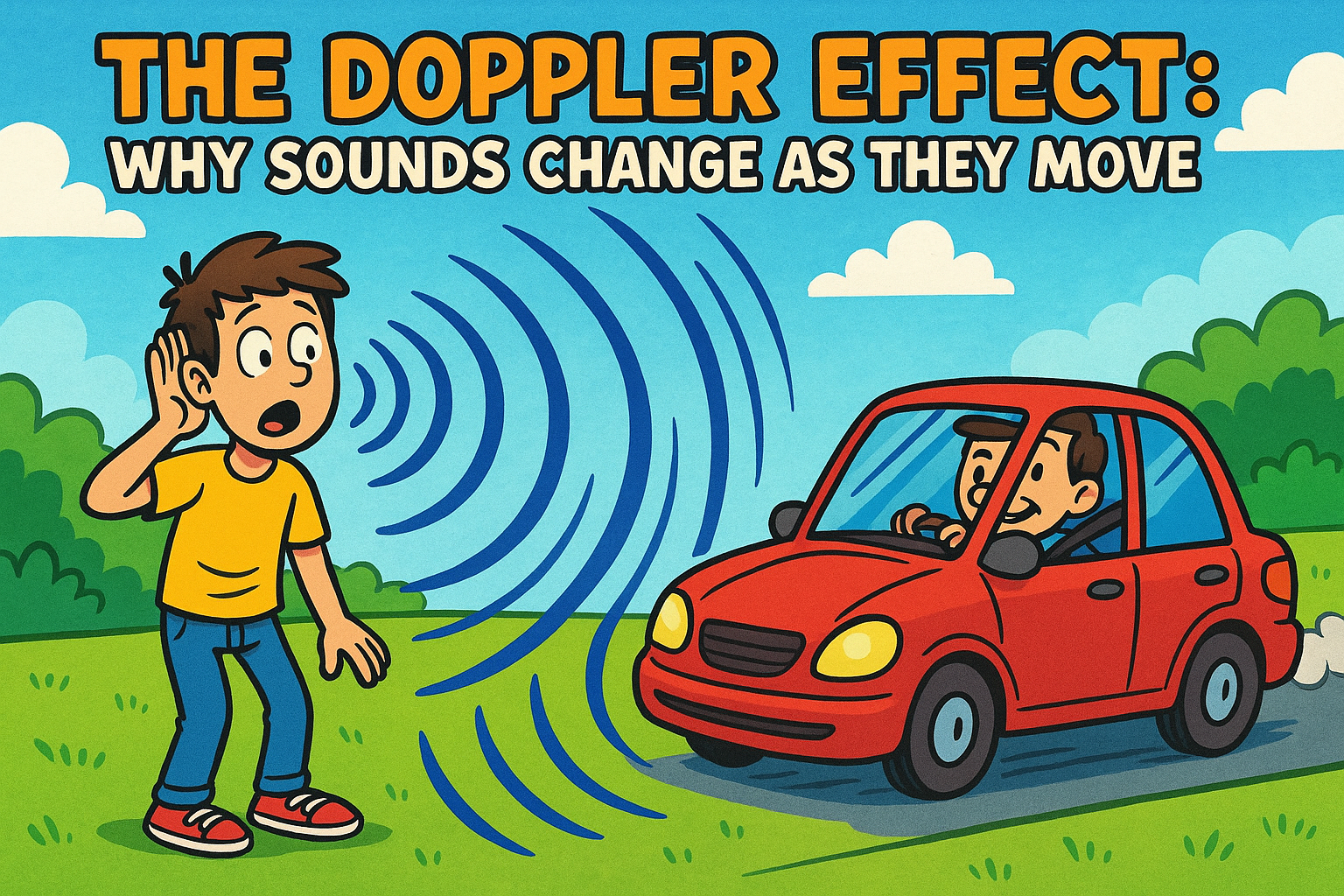

The Doppler Effect: Why Sounds Change as They Move

The Doppler Effect: Why Sounds Change as They Move

Have you ever noticed how a siren seems to change pitch as it passes by? That strange shift in sound is caused by something called the Doppler effect, and it’s the focus of this Doppler effect lesson. This topic helps us understand how sound behaves when either the source or the listener is moving. It links directly to how we hear, how we measure speed, and even how astronomers study distant galaxies.

The Doppler effect isn’t just about sound. It shows up in all kinds of waves—from ambulance sirens to radar guns, and even in how we track the motion of stars and planets. By understanding this, learners can get a deeper insight into how waves work in real life. They’ll also learn how our ears and brain interpret those shifts in pitch and frequency.

This lesson covers the basics of sound waves, what changes when things move, and why our position matters. It uses everyday examples, scientific reasoning, and simple models to explore a topic that’s surprisingly deep. The aim is to give a clear understanding of how wave behaviour connects with speed, motion, and our perception of sound. By the end, your learner won’t just hear the difference—they’ll understand it.

This topic is part of our Info Zone collection. You can read the full topic, once logged in, here: The Doppler Effect: Why Sounds Change as They Move

You’ll also find a full Lesson Plan and a handy Parent Q & A sheet, for this topic, ready to use..

What Is the Doppler Effect?

The Doppler effect is a change in the frequency or wavelength of a wave in relation to an observer who is moving relative to the source of the wave. It was first described by Austrian physicist Christian Doppler in 1842. Although it applies to all types of waves, it’s most commonly associated with sound.

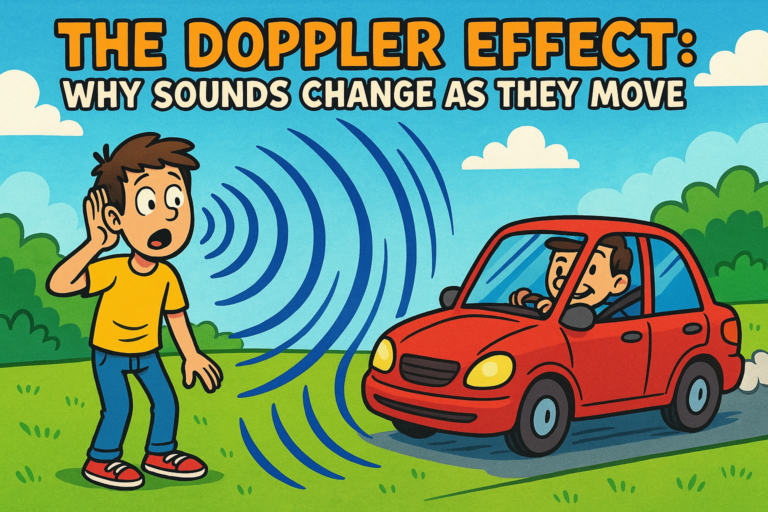

In simple terms, when a sound source moves towards you, the sound waves get compressed, causing the pitch to rise. When the source moves away, the waves stretch out and the pitch drops. This shift in pitch is a direct result of the **frequency change** in the wave pattern reaching your ears.

It’s important to remember: the speed of sound doesn’t change—it’s the wave spacing that changes. The actual air particles still vibrate at the same speed, but the number of wave crests that reach you each second depends on motion.

This idea links to the concept of a **sound wave shift**, where motion causes the wave pattern to distort. The Doppler effect helps explain why a siren changes tone as it races by or why a moving vehicle sounds different as it approaches and recedes.

The **Doppler effect lesson** gives us a practical example of how motion affects what we hear. Let’s break it down even further and explore the science behind it.

Understanding Sound Waves

Sound is a longitudinal wave that travels through a medium (usually air) as vibrations of particles. These waves have crests (compressions) and troughs (rarefactions), although in longitudinal waves they’re usually described as compressions and expansions along the direction of travel.

Frequency refers to how many wave cycles pass a point each second. Higher frequency means a higher pitch. Wavelength is the distance between compressions, and speed equals frequency multiplied by wavelength (v = f × λ).

In stationary situations, the wave spacing stays consistent. But when either the source or observer moves, things change. That’s where the Doppler effect comes in—when you move relative to the wave source, you experience a different wave frequency.

This also explains why bats and submarines use sound reflection and changes in wave frequency to navigate and locate objects. They rely on changes in reflected waves to tell how far or how fast something is moving.

In short, sound is just a pressure wave. When the source moves, those pressures bunch up or spread out. And we hear that as a change in pitch.

What Causes the Frequency Change?

The **frequency change** you hear in a Doppler effect situation depends on whether the source or the listener is moving. When the source comes towards you, each wave gets pushed closer together, which increases frequency. If it moves away, the waves get stretched out—frequency drops.

It’s important to understand that this isn’t about how loud the sound is. Loudness depends on amplitude, while pitch depends on frequency. The Doppler effect doesn’t make things louder or quieter—it just alters the tone.

Imagine a moving car honking its horn. To someone standing still, the pitch seems higher as the car approaches and lower once it passes. The horn itself isn’t changing—it’s the motion affecting the wave spacing.

If the listener moves towards a stationary sound source, they encounter more waves per second, increasing the perceived frequency. If they move away, they encounter fewer, and the pitch seems lower.

This change in pitch is known as a **pitch shift**, and it’s what our ears notice most. The Doppler effect is all about relative motion and how it skews the delivery of sound.

Everyday Examples of the Doppler Effect

One of the most common examples is an ambulance or police siren. As it approaches, you hear a high-pitched whine. As it passes and moves away, the tone drops noticeably. That’s the Doppler effect in action.

It also explains why a racing car sounds different coming toward you compared to when it zooms past. Aircraft, trains, and even fireworks display similar sound shifts as they move relative to where you’re standing.

Another example is radar guns used by traffic police. These use radio waves and bounce them off a moving vehicle. The **moving sound waves** reflect back at a different frequency, allowing the device to calculate speed.

Even weather radars rely on Doppler principles. They detect movement in storms by sending out waves and analysing how the frequency changes when reflected back.

So, next time you hear a changing pitch in real life, think about how motion—and the Doppler effect—plays a part.

The Doppler Effect in Light and Astronomy

The Doppler effect also applies to light. When light from an object in space moves towards us, its wavelength shifts towards the blue end of the spectrum (called “blue shift”). When it moves away, the light shifts towards red (called “redshift”).

This effect is critical in astronomy. Scientists can tell if a galaxy is moving away from us by measuring how much its light is redshifted. This is one of the key pieces of evidence that the universe is expanding.

Unlike sound, light doesn’t need a medium—it travels through space itself. But the same principle applies: the motion of the source affects the frequency of the wave received.

Redshift and blueshift are direct light equivalents of the pitch changes we hear in sound. They help us measure speed and distance on a cosmic scale.

This shows how the **Doppler effect lesson** connects small, everyday sounds to enormous, cosmic questions.

How Does Motion Affect the Wave?

When the source of a wave moves, the waves get bunched up in front and stretched out behind. Think of a swimmer creating ripples while moving through a pool—the ripples in front are closer together than the ones behind.

This bunching changes the wavelength (and therefore the frequency) of the wave that reaches the observer. Higher frequency means higher pitch or bluer light; lower frequency means lower pitch or redder light.

Even if the sound source isn’t moving but the observer is, the same effect happens. It’s all about the rate at which waves arrive at the listener’s location.

In equations, the Doppler effect for sound can be written as: f’ = f × ((v + v₀) / (v − vₛ)) Where f’ is the observed frequency, f is the original frequency, v is the speed of sound, v₀ is the speed of the observer, and vₛ is the speed of the source.

This equation allows scientists to calculate exact changes in pitch depending on motion—and it’s how many real-world instruments work.

Visualising the Doppler Effect

One way to imagine the Doppler effect is to picture a boat making waves. When it’s stationary, the ripples move out evenly in all directions. But when the boat moves forward, the ripples in front get squashed together and the ones behind stretch out.

This is exactly what happens with sound. The moving source creates wavefronts that are closer together in front (higher pitch) and farther apart behind (lower pitch).

You can also try a thought experiment: imagine you’re on a railway platform and a train approaches while blowing its horn. As it passes, the sound changes instantly. That shift happens at the moment the source moves past you—and it’s a perfect Doppler example.

Drawing wave patterns or watching slowed animations can help make this concept clearer. The wavefront compression and expansion is the core idea of the Doppler effect.

Understanding this visually helps connect the maths to what we hear and see in the real world.

Applications in Technology

The Doppler effect is used in a wide range of technology. Police radar guns, weather radars, ultrasound scanners, and sonar systems all depend on it.

In medicine, Doppler ultrasound is used to measure blood flow. By analysing how the frequency of reflected sound waves changes, doctors can tell how fast and in what direction blood is moving in the body.

In engineering, the effect is used in vibration analysis and machine monitoring. Any time waves are involved and motion is present, the Doppler effect may be useful.

It’s not just about sound either. Doppler shifts in radio waves help track satellites and spacecraft. Astronomers use redshift data to estimate the speed of distant galaxies.

The **Doppler effect lesson** isn’t just about understanding noise—it’s the key to understanding many tools we rely on every day.

Common Misunderstandings

One common mistake is thinking that the Doppler effect changes the speed of the sound itself. It doesn’t. The speed of sound stays the same for a given medium—it’s the frequency and wavelength that change due to motion.

Another misconception is that the sound source “sends out” different sounds in different directions. But it doesn’t. The source still produces a single tone—it’s just that motion changes how that tone is received.

Some people also confuse Doppler effect with echoes. An echo is a reflected sound, while Doppler is about motion and frequency change.

It’s helpful to separate what changes in the wave and what doesn’t. The wave speed is constant (in a fixed medium). What changes is how often the wavefronts reach you.

Getting this clear helps build solid understanding, especially when linking this to waves in light, water, or radio signals.

Why the Doppler Effect Matters

This topic links wave physics, motion, and real-world observation. It gives us tools to measure speed, distance, and direction—even without direct contact.

Whether you’re studying sound, ultrasound, space, or speed detection, the Doppler effect connects the theory to practice. It’s a great way to build deeper understanding of wave behaviour.

It also encourages learners to think critically. Why do we hear different things when we move? What does that tell us about how waves behave?

The **Doppler effect lesson** helps bridge everyday experience and scientific thinking. It’s a topic that opens doors—from police radar to cosmic expansion.

Let’s wrap up with some review and reflection.

A Final Thought

The Doppler effect shows how motion changes what we hear and see. It connects sound, light, and waves in a powerful way. And once you notice it—you’ll hear it everywhere.

Quick Quiz

- What causes the pitch to rise as a sound source approaches?

- What is the event called when wavefronts bunch up or spread out?

- Does the Doppler effect change the speed of sound?

- How does redshift relate to the Doppler effect?

- Give one example of Doppler effect use in medicine.

Write your answers in the comment section below.

Related Wikipedia Links

Explore more about this wave phenomenon and its uses:

What Do You Think?

If sound or light can shift based on motion, what other everyday things might change when objects move? Can we ever hear something before it arrives?